See also: When “No Case To Answer” means no accountability: Why the Tudor decision exposes a safeguarding system beyond repair

See also: Stephen Cottrell’s own words — and why they fail basic safeguarding and legal tests

See also: Archbishop Stephen Cottrell says he has been cleared — but the Tudor case is still under review

And if you want a good reminder of the case, listen to BBC Radio’s original File on Four investigation

The Archbishop of York, Stephen Cottrell, has issued a statement following the publication of the Section 17 decision in the David Tudor case. The tone is measured and pastoral, and the language carefully chosen. But read critically, the statement reveals not reflection, but entrenchment — and a continuing failure to address the structural safeguarding problem at the heart of the case.

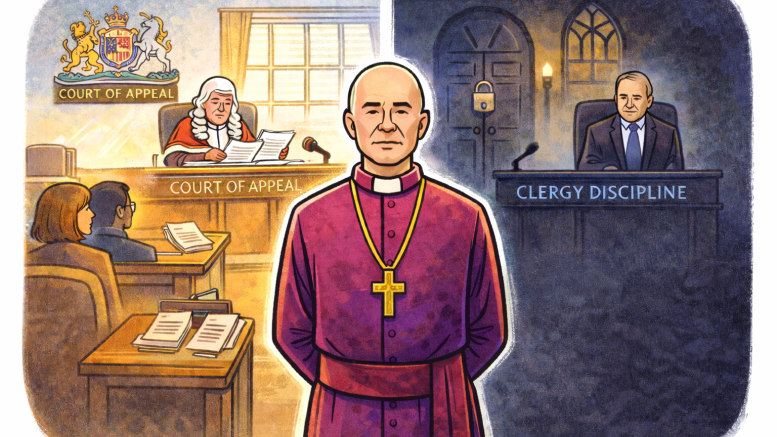

A striking feature of the statement is its emphasis on the fact that the President of Tribunals is a “Court of Appeal judge”. That fact is true, but its use here is deeply misleading.

The President was not sitting as the Court of Appeal. He was acting as a single decision-maker under the Clergy Discipline Measure — an internal ecclesiastical process that lacks the core features that give Court of Appeal decisions their authority. There was no public hearing, no adversarial testing of evidence, no full disclosure of documents to the complainant, and no robust appeal mechanism. The President’s decision was final in practice.

By contrast, the Court of Appeal operates with openness, procedural transparency, and institutional accountability. Parties have access to the evidence relied upon. Decisions are reasoned in public. Appeals are possible. The Supreme Court has repeatedly stressed that transparency is not optional in serious adjudication — most notably in Cape Intermediate Holdings Ltd v Dring, which underlined the constitutional importance of public access to documents underpinning judicial decisions.

Invoking the judge’s title while ignoring the procedural limits of the process is a clear warning sign. It seeks to appropriate the authority of a senior appellate court without acknowledging that the safeguards which give that authority its legitimacy — openness, evidential transparency, adversarial testing, and effective appeal — are absent from the processes established under the Clergy Discipline Measure. When Sir Stephen Males sits as a judge of the Court of Appeal, he operates under fundamentally different rules, procedures, standards of openness, and mechanisms of accountability than when he sits as President of Tribunals in clergy discipline proceedings.

A second and more serious concern appears in the Archbishop’s closing paragraph. He states that safeguarding standards have “changed and improved significantly since Mr Tudor was allowed back to ministry in the 1980s”.

That framing is profoundly problematic. The actions under scrutiny were not taken in the 1980s, nor in a period of undeveloped safeguarding awareness. They were taken decades later, when trauma-informed practice, victim-centred safeguarding, rigorous record-keeping, and sensitivity to power imbalance were already well-established expectations across public bodies, charities, and the Church itself. By relocating the issue to an earlier safeguarding era, the statement implicitly lowers the standard against which the Archbishop’s own decisions are to be judged. That is not an incidental choice of words; it reframes contemporary decision-making as if it belonged to a different moral and professional landscape, and in doing so deflects responsibility for actions taken in a period when better was both known and expected.

Most telling of all is what the statement does not say. The Archbishop once again relies on the claim that there was “no power” to remove David Tudor earlier. Yet he offers no indication whatsoever that he recognises this as a continuing structural failure, let alone that he intends to do anything about it. A bishop still cannot remove a priest in circumstances like Tudor’s. That prohibition remains. The statement contains no acknowledgement that this is unacceptable for safeguarding, no commitment to legislative reform, and no recognition of his own responsibility, as a senior Church leader, to address it.

Other red flags remain. The statement reiterates that decisions were taken “in accordance with advice”, without grappling with whether following advice absolves responsibility. It re-centres the narrative on the eventual suspension in 2019, while avoiding the harder questions about earlier choices to confer authority and honour. And it presents regret as sufficient, without analysing why those regrets did not translate into different decisions at the time.

Safeguarding accountability is not about tone, titles, or reassurance. It is about systems, evidence, and the willingness to confront uncomfortable truths. On that test, the Archbishop’s statement suggests that the most important lesson of the Tudor case has still not been learned.

Be the first to comment on "Authority invoked, lessons avoided: what the Archbishop of York’s statement still fails to confront"