If you don’t want to read the full 2,450 words, go to the 300-word TL;DR summary

The General Synod meets this week (starting tomorrow) for the first of three scheduled Groups of Sessions this year. It is the penultimate Group of Sessions this quinquennium, with the Synod being prorogued after the July meetings in York.

The November meeting marks the formal start of the next quinquennium: think of the State Opening of Parliament without the pomp, held every five years rather than annually. The King, as Supreme Governor of the Church of England, is expected to deliver a message to mark the formal opening of the new Synod with its newly elected or re-elected members.

The last opening of the Synod took place in November 2021. The current Duke of Edinburgh — then the Earl of Wessex — Prince Edward, stood in for the late Queen Elizabeth II and delivered the message she had written. It was the first time in the Synod’s 51-year history that Queen Elizabeth II missed the opening of a quinquennium. She had been advised to rest by doctors following a brief hospital stay the previous month.

When this quinquennium began, it did so with one of the biggest — if not the biggest — turnovers in membership. Many members, including me, had to get used to Synod processes, procedures and tactics. I say “tactics” because I soon discovered the lengths to which the Archbishops’ Council goes to curtail difficult debate, especially on safeguarding. Combined with a Business Committee that often appears to act as though it were the Archbishops’ Council’s business committee rather than the General Synod’s, the effect has been to blunt Synod members’ attempts to secure safeguarding reform that most people can see is needed.

Parliament says no

I believe that the Church of England is now at the centre of a governance crisis. Parliament’s Ecclesiastical Committee has ruled the draft National Church Governance Measure not expedient, rejecting the case for a new body that would concentrate more power and provide less accountability than the existing arrangements under the Archbishops’ Council.

We don’t know what MPs and peers made of the draft Measure, because the Ecclesiastical Committee cannot publish its report unless the Synod’s Legislative Committee signifies that it should be presented. Although the Legislative Committee has reported that the Measure was rejected, it has not, as yet, published the underlying report or set out the reasons.

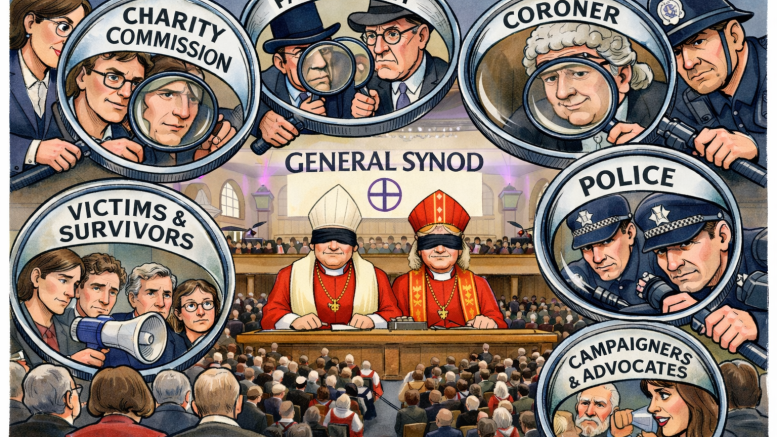

Alongside this, the Charity Commission is finally taking a harder line on the Church of England’s safeguarding failings. Over the past year it has:

- written to Synod members who are also charity trustees, reminding them of their safeguarding duties as trustees;

- written to diocesan bishops — who are Synod members and charity trustees — reminding them of similar duties and asking whether structural impediments prevent them from fulfilling those duties;

- warned the Archbishops’ Council that it must “rapidly accelerate” safeguarding reforms and meet an 18-month expectation, faster than the Council’s stated plans, including in its report to this week’s Synod;

- issued official regulatory warnings to two Diocesan Boards of Finance — Chelmsford and Liverpool — because their trustees (the bishop’s council) failed in their safeguarding governance and trustee duties in relation to allegations concerning the former Bishop of Liverpool, John Perumbalath.

For many years, the Archbishops’ Council has, in my view, relied on obfuscation and — more seriously — dishonest statements. Victims and survivors of church-related abuse have said this for decades. In recent years more campaigners and advocates have added their voices, and they have repeatedly been dismissed.

Now Parliament and the Charity Commission — the statutory regulator — have recognised what is happening and are signalling that poor practice must end.

How do the Archbishops’ Council respond? It defaults to type and continues to obfuscate.

They may get away with this approach with victims, survivors, campaigners and advocates. It won’t work against Parliament and the regulator.

Am I being too hard on the Archbishops’ Council?

A regular feature of General Synod is Question Time. Every Synod member may table up to two questions to several national Church bodies, including the Archbishops’ Council. Written answers are circulated shortly before the Group of Sessions begins, and each substantive question may attract up to two supplementary questions on the floor.

Let us look at two questions, and the written answers, for this Group of Sessions.

Janette Allotey, a lay member from the Diocese of Chester, asked the Presidents of the Archbishops’ Council — the Archbishops of Canterbury and York —this question:

“‘The Commission’s guidance is clear that trustees must take reasonable steps to protect from harm all people who come into contact with their charity.’ In the Regulatory Action Plan of November 2025 issued to the Archbishops’ Council following publication of the Makin Report, the Charity Commission expressed concern that the Church did not treat allegations of abuse from an adult not assessed to be vulnerable as a safeguarding issue. What steps, if any, are being taken to address this criticism?”

“Identifying the issues”

The written response came not from either archbishop but from a lay member of the Archbishops’ Council, Canon Alison Coulter. She wrote: “This is a matter that was also raised in the Charity Commission for England and Wales’s findings in relation to the Dioceses of Chelmsford and Liverpool. Staff of the Council are working to identify the questions, issues and requirements this raises and have written to the Charity Commission seeking a discussion on what changes may be needed. I will keep the Synod informed of progress and any changes required. However, Synod should note carefully the expectations that the Charity Commission has of trustees, of which they have helpfully reminded us.”

So: a Regulatory Action Plan in November, two Official Warnings to Chelmsford and Liverpool, and the Archbishops’ Council’s position is that it has written to the Charity Commission to seek “a discussion” while staff work to “identify the questions, issues and requirements” raised.

This response is extraordinary. The Charity Commission’s “questions, issues, and requirements” are not recent inventions. They reflect the legal duties that apply to every charity trustee.

Those duties are set out in the Charities Act 2011, which largely consolidates earlier charity legislation. The core obligations of trustees did not begin in 2011; they have been part of charity law for many years.

The Archbishops’ Council should already know what the Charity Commission expects of trustees, because those expectations arise from the law.

Perhaps, one might say, the Council is composed of well- meaning people acting in good faith who lack the specialist knowledge to navigate trusteeship. Maybe that is why it has written to the Charity Commission to seek a meeting.

A well-lawyered institution

That explanation does not withstand scrutiny. In July 2022, during my time as a Synod member, I asked how many lawyers the National Church Institutions (NCIs) employed, what they cost, and how many external lawyers they instructed for specific work.

The Secretary General, William Nye, replied that the number of legally qualified staff, and their immediate support staff, rose from 10 in 2017 at a salary cost of £935,078 to 13 in 2021 at a salary cost of £1,483,801.

On external lawyers, Mr Nye said that “the information requested is not readily available and could not be obtained without disproportionate cost.”

A brief aside on that claim. The Archbishops’ Council is a large charity. In 2021, the last year covered by Mr Nye’s figures, the council’s income was £128.09 million and its expenditure was £128.74 million. In 2024, published figures show income of £235.64 million and expenditure of £229.41 million.

An organisation of that scale does not run its finances on handwritten ledgers. It uses an accounting system with structured ledgers and cost centres that should allow external legal spend to be identified without disproportionate cost. On an ordinary reading, that is a basic requirement of financial control.

When Mr Nye said that the information “is not readily available” and could not be obtained without disproportionate cost, one of two things was true. Either the Archbishops’ Council was capable of producing the figure and chose not to disclose it (in which case Mr Nye lied), or it could not readily identify its external legal spend, in which case the trustees were not exercising proper oversight.

That aside illustrates the gap between the Archbishops’ Council’s claims to transparency and what it is prepared to disclose when pressed.

The larger point is that the Council cannot plausibly plead ignorance of trustees’ legal duties or of what the Charity Commission expects. It employs a substantial in-house legal function, and it spends well over £1 million a year on the salaries of legally qualified staff and their support.

Why, then, does the Archbishops’ Council present itself as needing to “identify” the Charity Commission’s “questions, issues and requirements”? Why does it need a meeting to establish what charity trustees are obliged to do?

The Regulatory Action Plan was issued in November last year. The Official Warnings to Chelmsford and Liverpool Diocesan Boards of Finance were issued last month.

These are unusual — and serious — interventions by the regulator, and I doubt they will be the last. Any organisation confronted with this level of scrutiny would normally treat it as a priority: trustees and senior officers would meet, identify the failures, and implement corrective action.

The Charity Commission’s intervention is not a “Lessons Learned Review” commissioned internally and filed away. It is a formal regulatory signal that practice must change. Incidentally, the Church of England no longer uses the “Lessons Learned Reviews” terminology. It now calls them “Safeguarding Practice Reviews” — an implicit acknowledgement, perhaps, that lessons have too often not been learned.

Janette Allotey’s question asked, directly, what steps were being taken to address the Commission’s November criticism. The written answer, as at February, was that staff were still “identifying” issues and seeking a discussion with the regulator. To me, that reads as an admission that the Archbishops’ Council do not have a firm grip on what charity trustees are required to do.

A letter seeking a meeting three months later raises obvious questions. Where is the urgency? Where is the action? Where is the change on the ground?

Another question for this week’s Group of Sessions is equally revealing.

Dr Brendan Biggs, a lay member from the Diocese of Bristol, also directed his question to the Presidents of the Archbishops’ Council. As with Janette Allottey’s question, the written reply came from Canon Alison Coulter.

Dr Biggs referred to the letter that the Charity Commission’s chief executive, David Holdsworth, sent to diocesan bishops in January 2025. It asked whether, after decisions taken by the General Synod in February 2025, there remained any “structural, procedural or constitutional arrangements under ecclesiastical law” that conflicted with, or prevented, bishops and their co-trustees from fulfilling their safeguarding duties as charity trustees (“legal impediments”). Dr Biggs asked whether bishops’ responses had collated centrally, and whether there was a plan to address any legal impediments identified.

Canon Coulter’s response illustrates, again, what I regard as a failure of the Archbishops’ Council — and of Diocesan Boards of Finance — to discharge basic trustee responsibilities.

She wrote: “Some dioceses have shared their responses with the staff of the Archbishops’ Council, but we have not produced a central digest.”

After referring to the Charity Commission’s November 2025 intervention, she added: “We continue to work with the Charity Commission on the Regulatory Action Plan and the Archbishops’ Council is determined to improve practice to fulfil our requirements. We very much hope that dioceses will work in partnership with us.”

That answer sits uneasily with her answer to Janette Allotey. In response to Ms Allottey, Canon Coulter said the Council had written to the Charity Commission to seek a discussion to understand what changes might be needed. Here she says the Council continues “to work with the Charity Commission on the Regulatory Action Plan”.

Which is it?

More seriously, the answer discloses a lack of proactive action. The Charity Commission’s January and February 2025 letters were public. Rather than treat them as a prompt for urgent, coordinated work, the Archbishops’ Council appears to have waited for the regulator to act and is now presenting itself as seeking clarity on what trustees are required to do.

What the Charity Commission expects is neither novel nor obscure. It expects trustees to fulfil their legal duties as trustees.

Instead of waiting, the Archbishops’ Council should have convened the bishops and asked them what “structural, procedural or constitutional arrangements under ecclesiastical law” prevented them from fulfilling safeguarding duties as charity trustees.

There is an obvious mechanism for doing that. The House of Bishops meets regularly, and this issue could, and should, have been on its agenda throughout the past year.

The General Synod has limited powers to initiate legislation. In practice, that is the preserve of the Archbishops’ Council. If “structural, procedural or constitutional arrangements under ecclesiastical law” must change to enable trustees of Church of England charities — including Diocesan Boards of Finance — to fulfil safeguarding duties, the Archbishops’ Council is the body that must bring forward the necessary legislation.

Independent charities — selectively

The Archbishops’ Council has often said that Diocesan Boards of Finance are independent charities and that it cannot require them to take particular action. The line that dioceses and DBFs are separate, independent charities has become a limiting principle: the Council does not, on that account, instruct, compel, or enforce outcomes, but relies on persuasion, encouragement, or legislative change.

Yet the Council invokes this principle selectively. In the second Past Cases Review (PCR2), dioceses were instructed on which files to review, the qualifications required of the reviewers, the actions expected of diocesan safeguarding teams, the timescale, the content of diocesan summary reports, and the manner of publication.

When asked to produce a report collating the recommendations made by reviewers across dioceses, the answer was that the Archbishops’ Council could not do this because the data belonged to those independent charities (the bishops’ councils).

This “don’t ask, don’t tell” approach is not legally defensible. Call it what you will — institutional blindness, deliberate ignorance, turning a blind eye, plausible deniability, or failure of oversight — the practical effect is the same: avoidance of responsibility and avoidance of scrutiny.

By failing to ask the questions that trustees ought to know must be asked, and by failing to require the information needed to discharge their duties, the Archbishops’ Council displays the same pattern that public inquiries have criticised elsewhere. In the criminal courts, directors who operate in this way may face exposure to corporate manslaughter investigations, health and safety prosecutions, and professional sanctions.

It is no longer good enough for the Archbishops’ Council to sit back and wait, suggesting that delay reflects a need for “clarity” from the Charity Commission. It must act — not because I demand it, and not only because the Charity Commission demands it, but because charity law requires trustees to act.

TL;DR — Synod questions expose a governance blind spot

Two questions at this week’s General Synod expose a deeper problem at the heart of the Church of England’s governance: how members of the Archbishops’ Council understand — or evade — their responsibilities as charity trustees.

In November, the Charity Commission issued a Regulatory Action Plan to the Archbishops’ Council following the Makin Report. It criticised the Church for failing to treat allegations of abuse from adults not assessed as vulnerable as safeguarding matters. Since then, the Commission has issued Official Warnings to two Diocesan Boards of Finance and written directly to bishops and Synod members reminding them of their legal duties as trustees.

Against that backdrop, Janette Allotey asked a simple question: what steps are being taken to address the Commission’s criticism?

The written answer was striking. The Archbishops’ Council said staff were still “identifying the questions, issues and requirements” raised by the regulator and had written to the Charity Commission to seek a discussion about what changes might be needed.

But the Charity Commission’s expectations are not new or unclear. They are rooted in long-established charity law. Trustees are required to act in the best interests of their charities and to protect people from harm. Those duties do not begin with correspondence from the regulator.

A second question reinforced the same picture. Asked whether bishops’ responses to the Commission’s letter about possible “legal impediments” had been collated centrally, the answer was no.

Together, these replies reveal a pattern of delay and deflection. Despite employing a substantial in-house legal team and spending well over £1 million a year on legally qualified staff, the Archbishops’ Council presents itself as needing “clarity” on what trustees are required to do.

That stance might once have gone unchallenged. With Parliament and the Charity Commission now watching closely, it no longer will.

Leave a comment