If you don’t want to read the full 2,450 words, go to the 300-word TL;DR summary

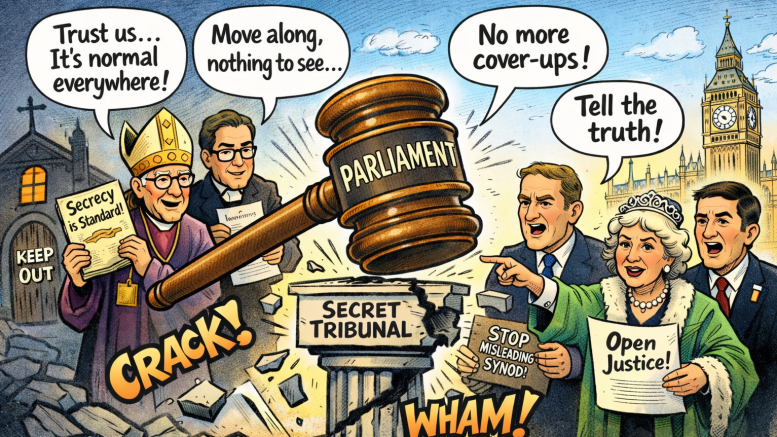

Why do the powers that be in the General Synod continue to mislead members about private or secret tribunal hearings being the norm?

That question sits at the heart of today’s Synod business on the Clergy Conduct Measure. Once again, members are being asked to take decisions on the basis of a claim that simply does not withstand scrutiny: that secrecy is standard practice in other disciplinary and professional tribunal systems, and that the Church of England is merely following an accepted model.

It is not.

It also matters to understand why this issue has resurfaced in today’s Synod agenda. The Legislative Committee is now asking Synod to reverse the presumption of private hearings and make public hearings the norm — but not because the Church’s leadership has suddenly accepted that it got this wrong. It is doing so because Parliament has forced its hand. The Ecclesiastical Committee has made clear that it will not allow the Clergy Conduct Measure to proceed to the House of Commons and House of Lords as expedient unless this change is made. In other words, Synod is being asked to fix a defect that Parliament has identified, not one that the Church was willing to acknowledge on its own initiative.

Crucially, the Ecclesiastical Committee did not stop there. In its scrutiny of the Measure, it also called for the Draft Rules to be provided to it — recognising, correctly, that the Rules will contain the real substance of the system: how complaints are handled, how hearings operate, what information is disclosed, and where secrecy is imposed in practice. The committee was plainly concerned that Parliament was being asked to approve a skeleton Measure while being denied sight of the operational detail that would determine how justice is actually done.

The Church’s response to that request has been to insist that Rules cannot be drawn up until after a Measure has been passed — language used repeatedly in evidence to the Ecclesiastical Committee. That position is wrong. It is contradicted by recent legislative practice within the Church itself. When Parliament considered the Abuse (Redress) Measure, the Legislative Committee did present Draft Rules to the Ecclesiastical Committee, precisely to allow informed scrutiny of how the scheme would operate in practice. The claim that this is impossible or improper is therefore not a matter of principle; it is a matter of convenience.

Repeating a false premise to Synod

In the report to today’s meeting, the Legislative Committee again relies on a partial transcript of Synod proceedings in which members were told that private hearings are the norm in other systems, including professional regulators such as the General Medical Council. That claim has been doing heavy lifting throughout the synodical process. It was used to neutralise concern, to truncate debate, and ultimately to justify making secrecy the default position in primary legislation.

But it is false. The constitutional principle of open justice means that tribunals exercising public functions sit in public unless there is a clear and specific justification for departure. Professional regulators do not reverse that presumption. They allow privacy by exception, not as a starting point.

This was not a matter of interpretation or opinion. Parliament was told exactly that when it examined the draft Measure.

Parliament was not persuaded

One peer cut straight to the point, questioning why a Church tribunal exercising statutory authority should depart from ordinary standards of open justice at all. Another asked why victims, complainants, and the wider public should be expected to trust a system that begins from privacy rather than transparency.

Most strikingly, Danny Kruger MP, drawing explicitly on a written briefing I had provided to committee members, challenged the comparison with professional regulators. He quoted from that briefing to make the point that the Medical Practitioners Tribunal Service lists hearings publicly as a matter of course, and that hearings are open unless specific reporting restrictions are imposed.

The committee’s scepticism was unmistakable. Members pressed Church representatives on why secrecy had been elevated into the Measure itself, rather than left to judicial discretion on a case-by-case basis. The underlying message was clear: Parliament did not accept that secrecy was either normal or necessary.

That scepticism ultimately found expression in the committee’s conclusion that the Measure was not expedient, precisely because it made private hearings the default.

“A very robust debate”? No, there wasn’t.

In oral evidence to the Ecclesiastical Committee, the Archbishops’ Council’s lawyer, Edward Dobson, attempted to reassure MPs and peers that Synod had consciously and robustly chosen this path. He told the committee:

“There was, during the course of the debate at General Synod, an amendment that sought to reverse that presumption… There was a very robust debate and the Synod decided to stay with this presumption.”

That statement mattered. It was designed to convey to Parliament that Synod had been fully informed, that arguments had been tested, and that secrecy was a deliberate, settled choice.

It was also untrue.

The amendment in question was never substantively debated. It fell because fewer than 25 members stood to allow debate to continue — after Synod had been told, incorrectly, that secrecy was commonplace elsewhere. A procedural lapse is not a debate, still less a “very robust” one.

Being called out — and doubling down

After the evidence session, I wrote to Mr Dobson asking him to correct the record. I set out why his description was inaccurate and reminded him that Synod members had been misled about other tribunal systems.

His response did not correct the record. Instead, it attempted to redefine events. He argued that an exchange limited to two speakers was sufficient to justify the description “robust”, and that the amendment lapsing: “in effect amounted to a decision by the Synod to retain the clause as drafted.”

That is simply wrong. Standing Orders explicitly distinguish between a debate on the merits and a failure to secure enough members to permit debate. One cannot be retrospectively converted into the other.

More tellingly, Mr Dobson’s response entirely avoided the central issue. He did not explain why Synod had been told that secrecy was normal elsewhere. Nor did he address the fact that the same false claim appeared in the written report of the Revision Committee.

When pressed again on that point, the silence remained

How many times does this need saying?

This was not the first warning, nor the second.

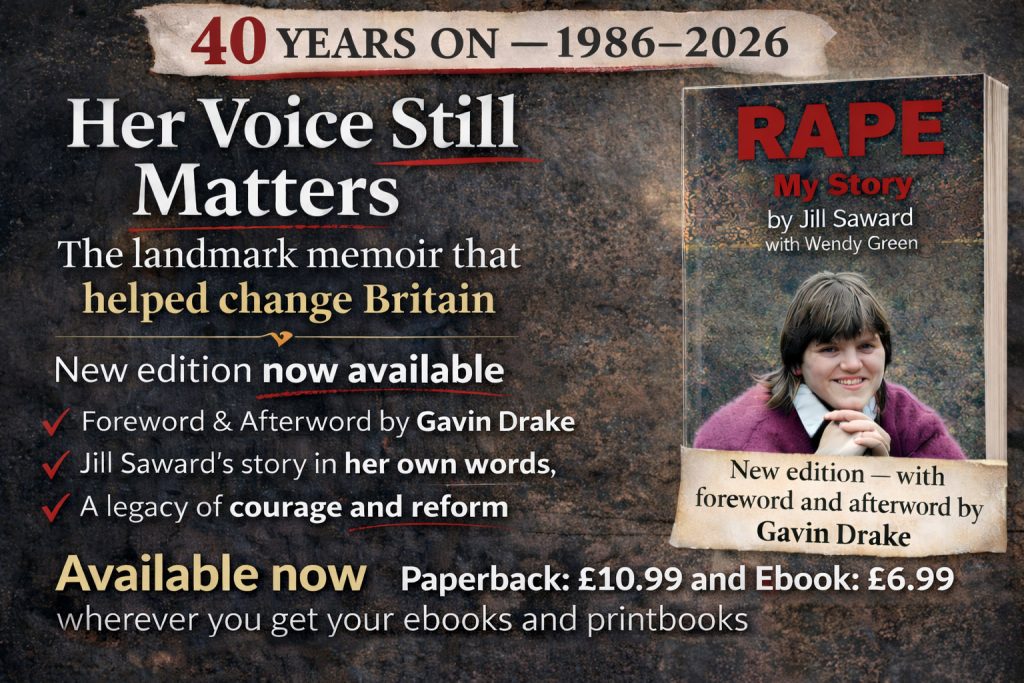

In July 2021, even before the Measure had been drafted, I prepared a formal briefing to Synod members on behalf of the Jill Saward Organisation, setting out why secrecy in clergy discipline had no sound legal basis, why open justice mattered, and how comparable tribunal systems operated transparently.

I have also repeatedly called out the false assertion in other posts here on churchabuse.uk, including:

- 25 July 2024 – “Archbishops’ Council lies about GMC in battle for secret clergy discipline tribunals”, documenting in detail how Synod had been misled about professional regulators.

- 15 August 2024 – “Archbishops’ Council ignored chances to fix safeguarding risk assessment loophole”, showing how opacity was being preserved by design.

- 15 January 2025 – “The General Synod and safeguarding – a look ahead to February’s group of sessions”, again correcting the false comparison with the GMC and explaining how professional tribunals actually operate.

Each time, the same claim resurfaced. Each time, it was wrong.

So why does it continue?

Which brings us back to the question that refuses to go away.

Why do the powers that be insist on giving Synod a misleading impression on this most fundamental point — about openness, justice, and trust — even after Parliament itself has exposed the claim as unsustainable?

And what does it say about the culture behind this Measure that, when falsehoods are identified and evidenced, the response is not correction, but entrenchment?

This matters because the issue is not simply one clause in one Measure. It is about whether Synod is being treated as a deliberative body capable of weighing evidence honestly, or as something to be managed through selective information and procedural sleight of hand. When members are told that secrecy is normal elsewhere, debate is truncated. When Parliament then exposes that claim as false, the response is not candour, but a reluctant concession forced by external scrutiny.

It also matters because secrecy does not protect justice; it protects systems. Victims and survivors do not gain confidence from processes that operate behind closed doors by default. Nor do clergy accused of misconduct benefit from a system in which outcomes are hidden, precedents are obscured, and public confidence is eroded. Open justice exists precisely to prevent error, arbitrariness, and institutional self-protection.

Synod is now being asked to correct a flaw that should never have been there in the first place — and only because Parliament has refused to wave it through. That should give members pause. If this much resistance has been shown to transparency at the level of primary legislation, what confidence can there be about how the system will operate once the detail is pushed into Rules, guidance, and practice directions beyond Synod’s effective reach?

So the question remains — and it deserves an answer. Why do the powers that be persist in giving Synod a misleading impression on so fundamental a point, even after being called out by Parliament? And until that culture changes, how can anyone have confidence that the Church’s disciplinary system is being designed in the interests of justice rather than institutional convenience?

TL;DR — Why Synod is still being misled about secret hearings

The General Synod is once again being asked to take decisions on the Clergy Conduct Measure on the basis of a claim that does not stand up: that private or secret tribunal hearings are the norm in comparable disciplinary systems. They are not.

This claim has been used repeatedly to justify making secrecy the default position in the Measure. Synod members were told that professional regulators — including the General Medical Council — routinely sit in private. That is false. Open justice is the constitutional norm. Other tribunals operate with public hearings as the default, allowing privacy only by exception.

The issue has resurfaced now because Parliament has intervened. The Ecclesiastical Committee has refused to allow the Measure to proceed to the House of Commons and House of Lords as expedient unless the presumption of secrecy is reversed. The Legislative Committee is therefore asking Synod to change course — not because the Church has acknowledged error, but because Parliament has required it.

The committee also demanded sight of the Draft Rules under the Measure, recognising that these will contain the real substance of the system. The Church’s response was to insist that Rules cannot be drafted before a Measure is passed. That claim is wrong. When Parliament considered the Abuse (Redress) Measure, Draft Rules were provided precisely to enable informed scrutiny.

During the Ecclesiastical Committee’s evidence session, members repeatedly challenged the secrecy default. Danny Kruger MP quoted directly from a briefing showing that professional tribunals are open by default. Parliament was not persuaded by assurances that secrecy was normal or necessary.

Despite this, the Archbishops’ Council’s lawyer told the committee that Synod had reached its position after a “very robust debate”. That claim is inaccurate. The amendment in question was never substantively debated; it lapsed after Synod had been misled about other tribunal systems.

Even when challenged directly, the response was not correction but defensiveness and entrenchment.

The question remains: why do the powers that be persist in misleading Synod on so fundamental a point — and what does that say about the culture behind this Measure?

Millstone or tombstone?

NON-DISCLOSURE AGREEMENT use can see senior clerics get ‘caught in their own snare’. PRIEST SHEPHERD FRIEND (https://share.google/yYRbZN3xCtqJMo51m ) appears at the end of a vicar’s tombstone inscription shown in this online link. The abuser priest lies in a grave by the Armagh cathedral seat of Archbishop John McDowell. One terminally ill victim received substantive legal compensation in 2023. But a controversial NDA perhaps prevents Archbishop John McDowell from formally naming and shaming the deceased abuser. The New Testament refers to “a millstone”-not an edifying tombstone-when referring to those who harm children. Anglicans should weep at what we see here.