If you don’t want to read the full 1,245 words, go to the 287-word TL;DR summary

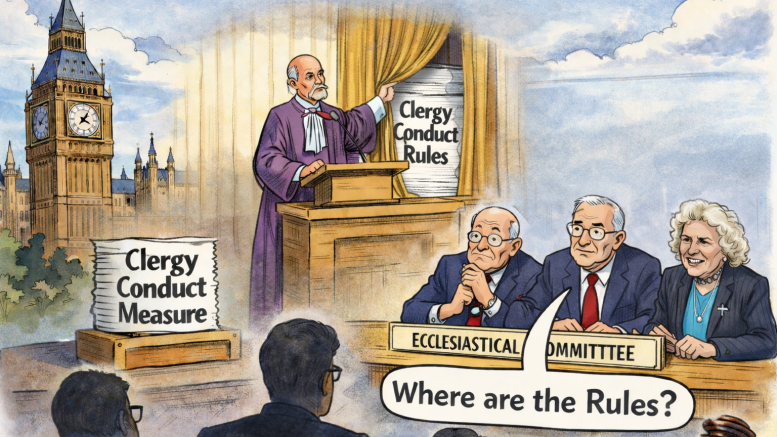

Yesterday’s votes at the General Synod on the Clergy Conduct Measure were inevitable. Once the Ecclesiastical Committee concluded that the Measure was “not expedient”, the Legislative Committee had little realistic choice but to amend clause 31(3) so that tribunals sit in public by default.

The amendment was always going to pass. It did. But inevitability does not mean that the underlying constitutional concerns have been resolved.

Indeed, the debate itself illustrated the deeper problem: how much of the system Synod and Parliament are being asked to approve is not contained in the Measure at all.

Parliament’s principal concern — but not its only concern

The Ecclesiastical Committee’s principal objection was the presumption of private hearings. The amendment reverses that presumption. That addresses the headline issue.

But the Committee raised further concerns: the absence of draft Rules, the lack of visibility over operational safeguards, and whether Parliament had sufficient information to judge expediency.

Those concerns were not technical. They go to the heart of the 1919 constitutional settlement.

Under the Church of England Assembly (Powers) Act 1919, the Ecclesiastical Committee must report on the Measure’s “nature and legal effect” and on its “expediency”. That duty cannot be discharged in the abstract. It requires understanding how the Measure will function in practice.

The Rules remain unpublished. The operational detail remains unseen. Parliament has still not been given what it repeatedly requested.

“Informal discussions” and constitutional silence

Speakers referred repeatedly to “informal” meetings between the Legislative Committee and the Ecclesiastical Committee. Such discussions may be convenient, but they are not provided for in the 1919 Act.

The 1919 Act establishes a formal legislative pathway: Measure, report, parliamentary scrutiny, approval motions in both Houses, and Royal Assent. It does not provide for private pre-legislative negotiation to substitute for formal scrutiny.

In UK constitutional culture, legislative scrutiny is conducted publicly. Evidence is published. Draft material relied upon by committees is ordinarily placed on the record. Opaque reassurance is not a substitute for visible accountability.

If draft Rules were shown formally to Parliament, they should be available publicly. If they were shown informally, Parliament should not be expected to legislate on that basis.

“Not within the function of the Ecclesiastical Committee” — and why that misses the point

Sir Robert Buckland told Synod: “Presenting a full set of rules to the Ecclesiastical Committee of Parliament risks usurping the vital role of this body in receiving, scrutinising and amending those rules before they go to Parliament.”

He continued: “Strictly speaking, the consideration of rules and other secondary legislation is not actually within the function of the Ecclesiastical Committee in any event.”

He further argued that rules: “can only ever be in draft as a matter of law, because the power to make them does not come into force until Royal Assent is given to the primary legislation.”

Formally, that has surface force. The Ecclesiastical Committee scrutinises Measures, not statutory instruments.

But that is not the Committee’s concern.

The Committee has stated that it must have sufficient information about how Measures are intended to work before it can declare them expedient. Where a Measure defers substantial operational content to Rules, those Rules are not peripheral. They are the mechanism through which the Measure takes effect.

The Clergy Conduct Measure is skeletal. It establishes offices, stages, and powers. But it leaves to Rules:

- the gateway requirements for complaints,

- the mechanics of investigation,

- the participation of safeguarding actors,

- the structure and content of reports,

- the detail of procedural protections,

- and the practical operation of hearings.

When Parliament is asked to determine whether legislation affecting legal rights is expedient, it must understand how that framework will function in practice.

If the practical safeguards, investigatory mechanics, confidentiality architecture and protections against vexatious complaints reside primarily in unpublished Rules, Parliament cannot realistically assess the Measure.

This is not Parliament intruding on Synod’s jurisdiction. It is Parliament attempting to discharge its statutory duty under the 1919 settlement. Framework legislation without operational visibility undermines meaningful scrutiny.

Why the CDM experience matters

This is not theoretical.

The Clergy Discipline Measure 2003 provides the cautionary example.

The Measure itself is consolidated and updated on legislation.gov.uk. But the Clergy Discipline Rules are not consolidated there. A composite version of the Clergy Discipline Rules is produced by the Archbishops’ Council. The Code of Practice and Statutory Guidance add further operational layers.

Over time, significant aspects of the discipline system have developed through Rules and Guidance rather than primary legislation:

- An “overriding objective” imported into the Rules.

- Confidentiality norms shaping pre-penalty proceedings.

- Publication removal periods set out in guidance rather than statute.

- A “minor complaints” process created in the Code but not expressly established in the Measure.

- Vulnerability assessments structured through Rules rather than primary text.

None of those features were debated in Parliament at the point of primary enactment.

The Clergy Conduct Measure is designed to replace the CDM. Its Rules, Code and Guidance will be drafted by the same institutional actors, through the same internal processes.

Parliament is therefore not being asked to approve a closed text. It is being asked to approve a framework that will later be populated by instruments it will never see.

That is precisely why the Ecclesiastical Committee requested draft Rules.

Uneven access and unanswered questions

Sir Robert Buckland also stated that “an indicative set of rules … about 75 per cent complete” had been supplied to members of the Ecclesiastical Committee.

Yet those Rules have not been published. Most members of Synod have not seen them.

If Parliament has seen them formally, they should be on the public record. If provided informally, Parliament should not be legislating on that basis.

The asymmetry is troubling: some appear to have access to material unseen by the majority.

A debate shaped from the top

Yesterday’s debate (you can read a transcript here) was front-loaded with senior office holders: the Bishop of Chichester, the Dean of the Arches, Sir Robert Buckland, the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Chair of the House of Laity — many members of the Legislative Committee itself.

When amendment 507 was debated, the Prolocutor of York spoke first. Immediately afterwards, the speech limit was reduced to three minutes.

The effect — whether intended or not — is that establishment voices frame the debate before ordinary members speak. That structure discourages dissent and narrows the space for scrutiny.

When scrutiny is already limited by the absence of draft Rules, this matters.

Public hearings “the norm” — but no apology

Several speakers emphasised that public hearings are the norm in other professions. That is correct. I have been arguing this for years. But for much of the Measure’s passage, Synod had been told the opposite.

The earlier assertion that private hearings were commonplace elsewhere has not been formally corrected or apologised for.

Transparency cannot be selectively rediscovered when Parliament insists upon it.

A rare correction — and a contrast

The Archbishop of Canterbury corrected an earlier misstatement during final approval. That immediate correction is to be welcomed. It reflects healthy parliamentary culture.

Such corrections should be routine. They should not require a speaker to be the subject of a formal complaint before realising a correction and apology is needed — as was the case with the Archbishop of York Stephen Cottrell last year.

The fact that a routine correction is worth noting says a lot about how the Synod is treated by senior officers of the Church.

Inevitable — but unfinished

The Measure now returns to Parliament with clause 31(3) amended.

But draft Rules remain unpublished. Informal discussions have substituted for visible evidence. Framework legislation continues to be advanced without operational transparency.

The Church has moved because Parliament required it to move.

That is necessity, not constitutional renewal.

TL;DR: Open hearings, closed details

Yesterday’s General Synod vote on the Clergy Conduct Measure was inevitable. Once Parliament’s Ecclesiastical Committee concluded that the draft Measure was “not expedient”, the Church had little choice but to amend it. The key change — reversing the presumption of private hearings — addresses Parliament’s principal concern.

But that does not resolve the deeper constitutional problem.

The Ecclesiastical Committee’s objections went beyond open hearings. It questioned the absence of draft Rules and the lack of visibility over how the system will operate in practice. Under the Church of England Assembly (Powers) Act 1919, Parliament must assess a Measure’s “nature and legal effect” and its “expediency”. That requires understanding how it will function in reality — not just reading its skeletal framework.

The Clergy Conduct Measure establishes offices and stages, but leaves critical operational detail to Rules that have not been published. Those Rules will determine how complaints are made, how investigations run, how safeguarding actors participate, what reports must contain, and how hearings function. If those safeguards and procedures are largely contained in unpublished Rules, Parliament cannot meaningfully assess what it is approving.

This is not theoretical. Under the Clergy Discipline Measure 2003, significant elements of the discipline system developed through Rules, Code of Practice and Statutory Guidance rather than primary legislation — including confidentiality norms, publication policies, vulnerability assessments and informal complaint processes. These were not debated in Parliament.

The Clergy Conduct Measure will be implemented by the same institutional actors using the same processes.

Parliament is therefore being asked to approve a framework whose real content will emerge later.

The Church moved because Parliament insisted. But draft Rules remain unpublished, informal discussions have replaced transparent scrutiny, and the core constitutional concern remains: legislation without operational visibility undermines meaningful accountability.

Leave a comment