In my last post, I accused the Archbishop of York, and the Archbishops’ Council, of lying about its decision to disband the so-called “Independent” Safeguarding Board, or ISB, and in particular, whether the vote to disband was unanimous. I also called into question the genuineness and sincerity of the archbishop’s apology for misleading the General Synod.

As I said in that post, it was a meaningless lie – the decision had been taken and it made no difference whether the decision was unanimous or not. But still the lie came.

What happens when a lie does make a difference? What happens when a lie is being used to prevent debate on a proposed amendment to a new law? Such a lie was told at the General Synod in July.

Before I go onto that, I must give two small pieces of background.

The first piece of background is a brief history lesson: In 1919, Parliament devolved law-making powers to the Church of England. Through the Church of England Assembly (Powers) Act, the General Synod can pass Measures. These are sent to a joint committee of both Houses of Parliament. If the Committee assess the Measure as being “expedient”, it goes to the House of Commons and the House of Lords for a vote – often without debate – and then to the monarch for Royal Assent.

Once passed, a Church of England Measure becomes primary legislation – with the exact same status in law as an Act of Parliament. The General Synod can even amend actual Acts of Parliament through a Measure. So they are important. And so is the process of how draft Measures are debated, scrutinised, revised, and passed. That’s the history lesson.

The second piece of background is a current affairs update! One Measure, which has proved to be very controversial, is the Clergy Discipline Measure 2003. This sets out how complaints against clergy are to be dealt with. It is an appalling piece of legislation which has been criticised in equal measure by those who have been subject to a complaint and by those who have made complaints.

While passed in 2003 the Clergy Discipline Measure didn’t come into full operation until January 2006. This is because a clergy discipline Commission needed to be set up and the Commission had to formulate rules which are secondary legislation – Statutory Instruments – to set out how the Measure would be operated. Once in operation, the obvious flaws in the Measure became apparent – and to be fair, many of these were already apparent and were raised but dismissed in the Synod debates about the 2003 measure. Complaints were numerous, and include:

- the way different bishops apply the rules differently in the early stages of the complaints process;

- the removal of the bishop’s role of “chief pastor” to clergy facing complaints (how can a bishop administer pastoral support while also making disciplinary decisions);

- the creation of a “code of practice” which is supposed to say how the Measure and Rules are implemented, but which goes far beyond the power given to those responsible for drawing up the code (it goes so far as to pretend people could be referred to the High Court for contempt if they talk about a complaint brought under the measure);

- the secrecy surrounding the process; and

- the perceived weaponising of the process.

A lengthy official consultation took place alongside unofficial work by bodies such as the Ecclesiastical Law Society and the Society of Mary and Martha, a clergy support organisation based at Sheldon in Devon. The various strands of work were woven together by the Archbishops’ Council to create a Draft Clergy Conduct Measure. And the General Synod agreed that the Clergy Discipline Measure should be replaced by the new Measure.

That’s the background. And now the detail:

In Parliament, draft primary legislation is called Bills and when passed they become Acts. In the General Synod the language is less distinct. Once passed draft legislation becomes Measures and before they’re passed they’re simply called Draft Measures. I explain this to avoid confusion. At this stage the draft Clergy Conduct Measure should be called just that – a Draft Measure – and I hope that I maintain that distinction as I continue.

The CCM – the Clergy Conduct Measure – was introduced into Synod for first consideration in July 2023. This was a general debate on the principles of the Measure. After this, it was referred to a revision committee, which is a small group of Synod members appointed to consider each clause of the draft and also to consider revisions proposed by other Synod members.

Synod member Clive Scowen is a barrister. He works at the Incorporated Council of Law Reporting for England and Wales. This is the body that collates and records decisions of the higher courts – those courts whose decisions on questions of law are binding on lower courts. He proposed an amendment which would make tribunal sitting public as the default, but with the power for tribunals to sit in private or to make reporting restrictions in cases where it was appropriate.

The revision committee rejected this amendment and in its report to the Synod explaining its decision it said: “it was noted that other professional tribunals such as General Medical Council hearings sit in private due to the confidentiality of patient information”.

With the proposed amendment falling in the revision committee there was one more chance for Mr Scowen to propose his amendment during the revision stage debate on the floor of the General Synod.

And he sought to do so. He said: “The Measure as drafted makes it the default that proceedings under it should be heard in private. This amendment seeks to reverse that default. Proceedings would be heard in public unless the tribunal or court was satisfied that it was in the interests of justice to sit in private. . . Now of course there must be provision for those exceptional cases where the interests of justice are not served by a public hearing. But I suggest that the confidence in this new system and the interests of justice generally requires public hearings; and that private hearings should be very much the exception rather than the rule”.

The revision committee again rejected the proposed amendment. The Reverend Canon Kate Wharton, a member of the Archbishops’ Council, is the chair of the steering committee set up for the Draft Measure, and as a result of that is also a member of the revision committee. Telling Synod why the committee continues to oppose the amendment she said: “it is worth noting that sitting in public does not mean sitting in secret. It merely means that the public and press are not able to attend the hearing unless one of the exceptions applies. This is very commonplace in other disciplinary proceedings such as cases involving medical professionals where confidential material is often discussed”.

Within the next few days I will publish a further blog post and video about the importance of open justice and how this is a fundamental principle of English law – a principle repeatedly upheld by the UK Supreme Court when hearing challenges about access to tribunals and court documents. But for today I want to concentrate on the claim that the position taken in the Measure is commonplace.

Because this is a lie.

A quick recap: the written report said other professional tribunals, such as General Medical Council hearings, sit in private due to the confidentiality of patient information.

Kate Wharton said that the default being closed tribunals is “very commonplace” in other disciplinary proceedings such as cases involving medical professionals where confidential material is often discussed.

Both statements are lies.

Firstly, the GMC doesn’t hold tribunals. It investigates complaints and if concerns are serious they’re referred to the Medical Practitioners Tribunal Service. Like the CDM, and the CCM if passed, the process for the GMC / MPTS is set out in law. And the law requires such tribunals to be held in public. And the MPTS website provides details of current and upcoming hearings.

Other medical professionals who aren’t doctors may be referred to the Health and Care Professionals Tribunal Service (HCPTS) for allegations of misconduct. The HCPTS maintains an online published calendar of forthcoming hearings which are held in public.

Both the MPTS and the HCPTS can exclude the press and public where it is necessary in the interest of justice or to protect vulnerable witnesses, including victims of misconduct. They can also impose reporting restrictions.

The amendment proposed by Clive Scowen would have brought the Church of England in line with these procedures, which is: a starting point that tribunals are held in public but with the power to move to closed hearings where necessary. This – because of the basic principle of English law withheld many times by the Supreme Court – is the standard position of most tribunals

If the Archbishops’ Council want to continue with secret tribunals it should say so. But why lie and mislead the Synod into thinking that what they are proposing is the norm? Even falsely citing other tribunals.

Under the synods procedural rules, an amendment to draft legislation opposed by the revision committee falls unless 25 members stand to support it. When this was debated in the Synod, 25 members did not stand and Mr Scowen’s amendment fell without debate. The Synod rejected the amendment after being falsely told that the draft legislation adopts the practice of the GMC.

We don’t know if 25 members would have stood if they had been told that the CMC would be an outlier in terms of other tribunals; but the fact is the decision they took followed receipt of false information both orally and in writing.

I put this to Canon Wharton. I anticipated that she would acknowledge the error and confirm that she would inform Synod of the misinformation. She did not respond to my questions, which included asking who told her that GMC hearings are held in private

I put the same question to the Archbishops’ Council’s communications team. I also asked what options existed for Synod members to challenge and if they so wish to debate the amendment before final approval. They declined to answer either question but the director of communications did provide a statement. She said:

“Neither the revision committee report, nor Canon Wharton, said to Synod that tribunals which operate under the auspices of the GMC sit in private as the default position.

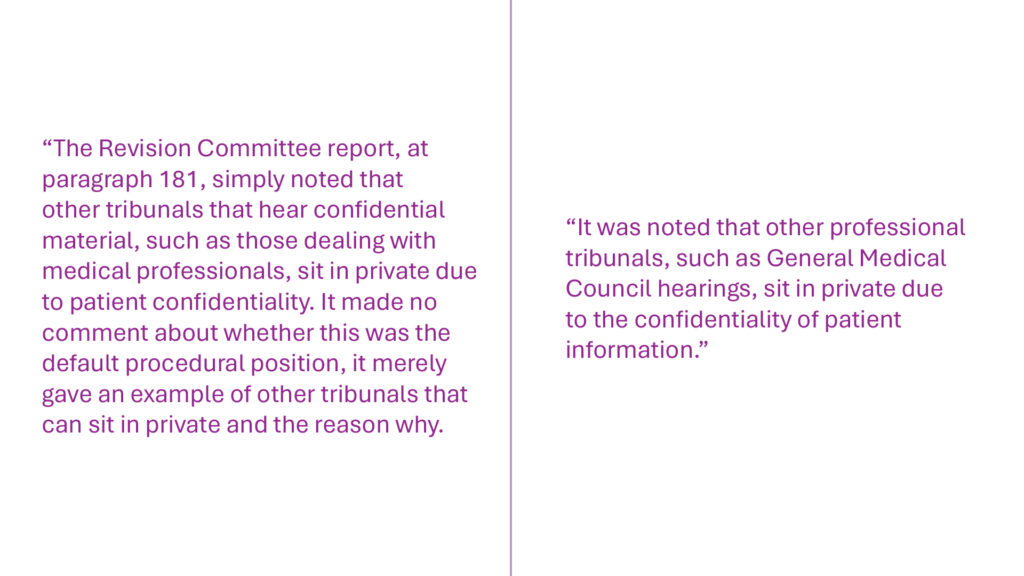

“The revision committee report, at paragraph 181, simply noted that other tribunals that hear confidential material, such as those dealing with medical professionals, sit in private due to patient confidentiality. It made no comment about whether this was the default procedural position, it merely gave an example of other tribunals that can sit in private and the reason why.

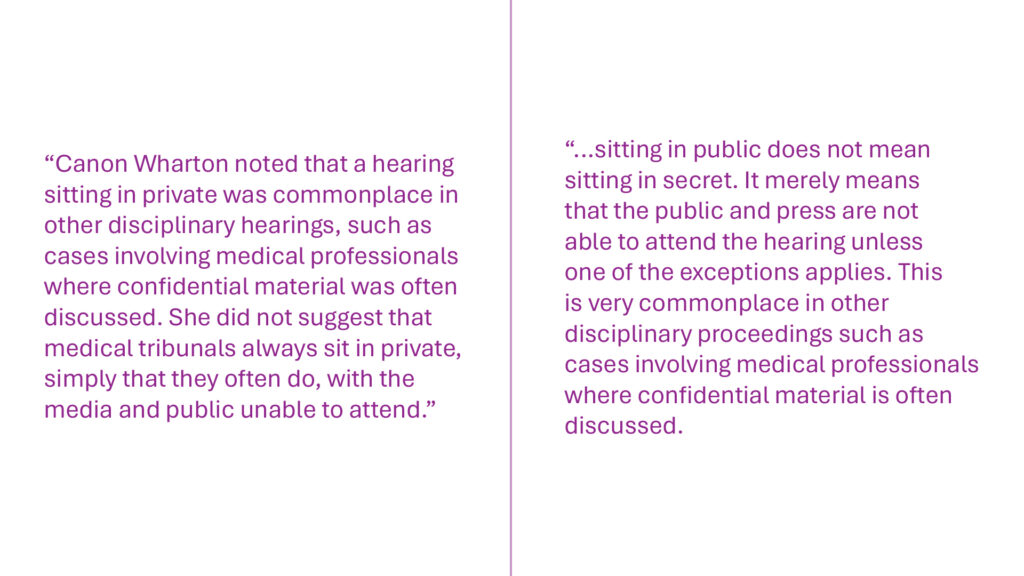

“In the discussion on Mr Scowen’s proposed amendment Canon Wharton noted that a hearing sitting in private was commonplace in other disciplinary hearings, such as cases involving medical professionals where confidential material was often discussed. She did not suggest that medical tribunals always sit in private, simply that they often do, with the media and public unable to attend.”

I’m used to the Archbishops’ Council lying; but even I’m incredulous at this response which seeks to rewrite history – recent history that is supported by documentary evidence.

It is a blatant lie.

Let’s look at two separate parts of the statement.

On the revision committee report. The Archbishops’ Council’s director of communications said: “the revision committee report at paragraph 181 simply noted that other tribunals that hear confidential material such as those dealing with medical professionals sit in private due to patient confidentiality. It made no comment about whether this was the default procedural position it merely gave an example of other tribunals that can sit in private and the reason why.”

What the committee report said is: “it was noted that other professional tribunals such as General Medical Council hearings sit in private due to the confidentiality of patient information”.

The report doesn’t say that GMC hearings can sit in private. It says that they do sit in private. And without providing any qualification to the claim that GMC hearings sit in private, the report is saying that this is the default position.

On Canon Wharton’s oral response to Mr Scowen’s amendment at Synod, the Archbishops’ Council’s director of communications said: “Canon Wharton noted that a hearing sitting in private was commonplace in other disciplinary hearings such as cases involving medical professionals where confidential material was often discussed. She did not suggest that medical tribunals always sit in private simply that they often do with the media and public unable to attend.

But what Canon Wharton actually said, is: “sitting in public does not mean sitting in secret. It merely means that the public and press are not able to attend the hearing unless one of the exceptions applies. This is very commonplace in other disciplinary proceedings such as cases involving medical professionals where confidential material is often discussed.”

Canon Wharton did not say that hearings in private are commonplace. What she said was commonplace, was that tribunals sit in private unless exemptions apply. And again, there was no qualification she said that other disciplinary proceedings such as medical matters routinely sit in private. They don’t.

I was happy to give the benefit of the doubt to Canon Wharton’s oral response to Clive scowen, and also to the written report of the revision committee. After all, if the committee and Canon Wharton had been misled themselves, they could only go on the information they had received; but Canon Wharton hasn’t answered my question about who told her this information.

But the benefit of the doubt can no longer be applied. When the Archbishops’ Council’s communications director issues a statement which fails to acknowledge that – potentially inadvertent – misinformation; and instead doubles down by stating that a written text doesn’t say what the written text says; and that a recorded oral response doesn’t say what was recorded; then only one conclusion can be drawn:

It is another Archbishops’ Council lie.

- Stay tuned for my next post, in the coming days, which will explain why openness and transparency is important, and why Clive Scowen’s amendment should be passed.

I think there is a mistake in this sentence; “Telling Synod why the committee continues to oppose the amendment she said: “it is worth noting that sitting in public does not mean sitting in secret”

Sitting in private surely?

I agree, but this is a direct quote. I assume that it was a slip of the tongue.

Gavin, this is quite excellent and VERY well produced. Chris

It is wildly inaccurate. I sit as a professional conduct tribunal member (judge) for more than one of the statutory and/or professional regulators. It is one of the central principles of these tribunal proceedings that hearings are held in public unless there is good and sufficient reason to hold them in private. Applications can be made to hear the whole case in private, but these are very rarely successful, because a public interest test must always be applied, and in the vast majority of cases, this trumps any reason for hearing the entirety of the case in private.

What usually happens is where there is confidential evidence or mitigating information – usually sensitive medical information about the defendant, complainant (if an individual), and/or a witness- or where there is a vulnerable witness to be protected, the part of the hearing where this evidence is disclosed and questioned is heard in private, and the remainder in public. Panels are adept at this switching during a hearing, as are counsel.

I can confidently say that the regulators I undertake this role for do not hear hearings in private just to protect the reputations of the defendant, complainant or the organisation for which they work. So it is utterly inaccurate for Canon Wharton to claim there is any precedent for a policy of private hearings as normative among the professional and statutory regulators.